The Customer Centricity Manifesto: Leverage Customer Lifetime Value to Create a Winning Strategy

March 22, 2019

"Companies are struggling to turn today's wealth of information into actionable insights that drive value for their organization—and for customers—because frankly, most business approaches to sales, marketing, data analytics, and finance remain stuck in a bygone era."

In 2012, when Guggenheim Baseball Management arrived as the new ownership group for the Los Angeles Dodgers, things were far from perfect.

Even though the Dodgers are fortunate to have a devoted fan base and the second largest market in the sport, Forbes listed their revenues back then as tied for sixth in Major League Baseball.

The new ownership group got to work right away on transforming the team and the business, and made the smart decision to hire Royce Cohen, now vice president of business development and analytics. Cohen is fanatical about two things in life: baseball and data.

When he joined the Dodgers in 2014 and looked around for opportunities to improve the business, he was struck by the absence of an enterprise Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system and that ticket sales were mostly managed using Excel.

On the bright side, the lack of sophisticated business intelligence systems presented opportunities for the Dodgers to build an analytics stack from scratch in a way that was system agnostic. Cohen told us that “this forced us to think about the problems we want to solve with data in a way that isn’t dictated by the system we want to work in.”

One of the earliest projects for the business analytics team was an ambitious Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) segmentation study. While the data teams at most baseball organizations were leaning on the observable characteristics of their customers, like personas and demographics that we warn against in our book, The Customer Centricity Playbook: Implement a Winning Strategy Driven by Customer Lifetime Value, Cohen believed strongly in the approaches Peter was proving out in study after study about CLV.

Unfortunately, this first attempt wasn’t the smashing success Cohen had hoped, because he and the team faced a myriad of challenges relating to limited historical data about customers. But they persisted, building out the data warehouses, analytics, and other business intelligence infrastructure that were required to model CLV effectively. Now, with five extra years of rich customer data, they have been able to realize their original vision.

As Cohen explains, the business of ticketing is commonly summed up by three questions:

- “How many tickets will sell?”

- “At what price?”

- “And in response to which promotions?”

He has been on a mission to add a fourth question: “To which customers?”

Once you have reliable models that accurately reflect the heterogeneous makeup of your customers—which the Dodgers now have and rely on—it’s easier to analyze these tightly linked questions in integrated ways, and thus better understand the varying propensities of your customers with respect to buying and price points.

In practice, confidence in these models has translated into numerous innovations for the Dodgers’ various acquisition, retention, and development tactics. For instance, in 2018 they launched a new two-tiered early season ticket renewal offering. The first tier is aimed to further develop the value of their longest-standing, highest-paying customers who are proven to be loyal, less price sensitive, and thus happy to pay extra for their season tickets in exchange for a number of desirable benefits (like batting practice on the field and deals at the concession stand).

On the other hand, the second tier skews more heavily to season ticket holders who have had seats for less than 10 years and may be paying a lower-average price per seat. For this tier, the main additional perk is offering the same price for the following year, making this more of a retention play.

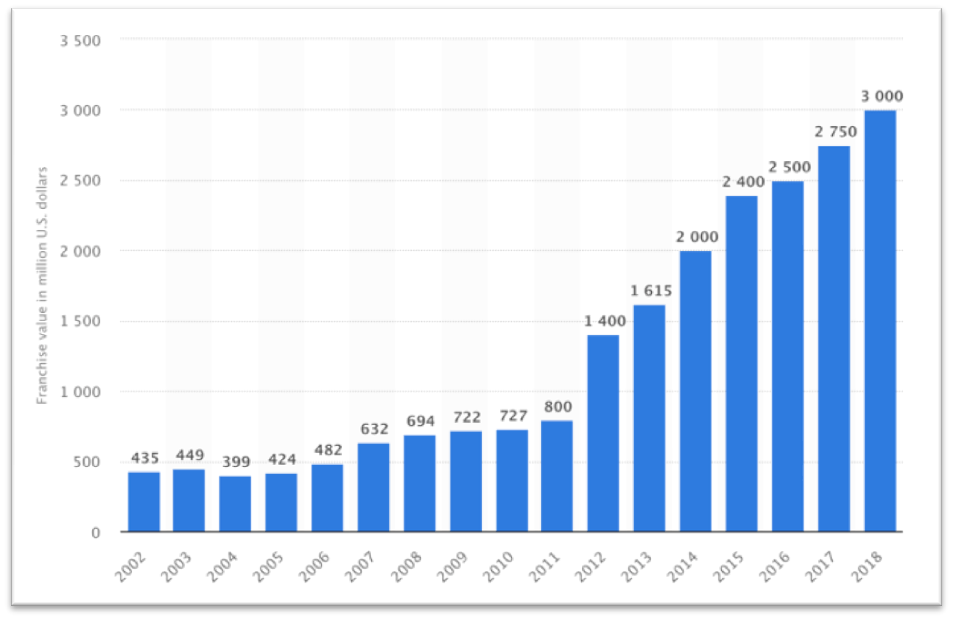

The results of the Dodgers’ improved business strategies are best reflected in the numbers. In the past five years, the team has doubled annual revenue, moving up to second place in the earnings leaderboard for the league. And in the past seven years, the team has doubled its valuation to 3 billion U.S. dollars.

Franchise Value of the Los Angeles Dodgers, 2002–2018 (millions of US dollars)

Source: “Los Angeles Dodgers franchise value from 2002 to 2018 (in million U.S. dollars),” Statista, Accessed February 20, 2019

It’s important to share the Dodgers’ success story because it shines a light on some specific areas where many companies continue to flounder in an era when the cost to collect and store data about customers is at record lows. Across the spectrum, companies are struggling to turn this wealth of information into actionable insights that drive value for their organization— and for customers—because frankly, most business approaches to sales, marketing, data analytics, and finance remain stuck in a bygone era. Given this mounting tension between the opportunity that having readily available information about our customers should be providing and the desperation caused by outmoded business practices that aren’t engineered to deliver customer centric insights, we decided to look at another industry that successfully overcame similar challenges.

“Companies are struggling to turn this wealth of information into actionable insights that drive value for their organization—and for customers— because frankly, most business approaches to sales, marketing, data analytics, and finance remain stuck in a bygone era.”

A Manifesto for Customer Centricity

At the dawn of the dot-com heydays, most software developers were growing increasingly fed up with the convoluted, bloated processes used at the time for software development projects. Sarah was running her own tech startup at the time, developing custom software for large multinationals, and shared similar frustrations about the arcane software engineering processes that made it difficult to develop high quality software in line with business needs and expectations. Luckily for her and others in the industry at the time, in 2001 several maverick technologists decided to publish their revolutionary Manifesto for Agile Software Development: a bold proclamation that launched radically new approaches to how software—and now technology and products in general—is developed and maintained.

That got us thinking: What would a manifesto for customer centricity look like? We came up with our own (if you’d like to add your name as a signatory, go to customercentricitymanifesto.org).

By wholly valuing, investing in, adopting, and endorsing items on the left, we aim to develop and implement winning strategies that best leverage customer lifetime value:

- Customer Heterogeneity over the Average Customer

- Cross-Functional Uses of CLV over siloed applications

- Metrics That Reflect Customer Equity over volume and cost obsession

- Clear Communications with External Stakeholders over misalignment and misunderstanding

Customer Heterogeneity

Back in the 1950s, when marketing emerged as a critical function for product-centric firms to keep demand in line with supply, businesses started to notice that their customers were inherently different from one another.

This discovery was a nuisance because it meant that one-size-fits-all approaches to marketing, while cost-efficient, were no longer feasible. So businesses had to start differentiating their messaging and product offerings—but they’ve tried to do so as little as possible to keep the costs down.

Thankfully, there has been a 180 in thinking since those times—companies are starting to see that these differences across customers provide an opportunity to make more money by targeting the right customers and investing in them to develop long, profitable relationships.

A number of years ago, Peter worked with a small manufacturing company whose CEO truly believed in customer centricity. But the CEO grew frustrated by his staff who remained frozen in a product-centric mindset and habitually referred to “the” customer. So the CEO came up with a clever way to call attention to this bad habit.

He placed a fishbowl at the front desk, and anytime someone in the company referred to “the” customer, they had to put a dollar in the bowl. It was a simple but very visible way to bring this important point across, day after day. Employees started listening carefully for the offending words, and there was always a lot of lighthearted buzz around the office whenever anyone would catch a colleague referring to customers in some kind of average or singular manner. Then, at the end of the year, the CEO used those funds (with some more of his own) for a “Celebration of Customer Heterogeneity” party. What a great way to reinforce this key idea (and the practices that arise from it).

Cross-Functional Uses of CLV

A truly customer-centric firm will seek to establish a variety of use cases across the organization that demonstrate the strategic advantages that a focus on CLV (and related predictive analytics) can provide.

According to Peter, this was one of his greatest joys in running Zodiac, the predictive analysis firm he cofounded in 2015 (and sold to Nike in 2018). Besides the standard acquisition/retention/ development use cases (e.g., determining which email to send to which customer at which time), many clients would dream up new use cases that Peter and colleagues hadn’t thought of.

Examples include salesforce compensation/incentives, new product evaluation (based on the CLV of customers who try it), promotional campaign assessment, and providing guidance to research and development teams to help them create products that will best appeal to highvalue customers. And of course, there’s the idea of customer-based corporate valuation to win over the finance and accounting staff—more on this in a moment.

In general, it is essential to get cross-functional buy-in for customer centricity (or any strategy) to succeed, and there is no better way to do so than to make it incentive compatible for as many employees as possible to embrace CLV to make their own job performance better.

“Companies are starting to see that these differences across customers provide an opportunity … ”

Metrics That Reflect Customer Equity

Perhaps the leading customer metric used by businesses today is Net Promoter Score (NPS). It might not be the ultimate metric, but it’s been a great way to get C-level executives to start to appreciate the differences across customers (in this case, the relative proportion of “promoters” vs. “detractors”). Building on the spirit of NPS, we want to see firms adopt a broader set of metrics that directly or indirectly reflect customers’ propensities to be acquired, buy repeatedly, maintain the relationship, refer others, respond to the right messages, and more.

We know these propensities can be hard to measure and are deeply intertwined, making efforts to study them more complex and error prone, but there seems to be sincere interest on the part of many executives to make this happen.

It’s important to take these first steps in a careful manner. In some of his work on customerbased corporate valuation, Peter (along with his former PhD student Dan McCarthy of Emory University) has looked at various metrics that firms occasionally report (sometimes informally, other times in more formal financial statements). These include some fairly self-explanatory metrics such as quarterly total orders and quarterly active users, as well as some more complex ones, like percentage of current orders arising from repeat-buying customers.

It is very important for firms to understand how these and other emerging metrics relate to CLV (and all the way up to corporate valuation). First and foremost, this exercise should be done for internal purposes: Going back to the cross-functional use cases just discussed, which aggregate metrics to best reflect the effectiveness of each of these activities? Obviously a firm doesn’t want to overcomplicate its performance scorecard, but executives will surely need an array of customer metrics to reflect the different ways that CLV (and customer centricity in general) is creating value across the organization. And once these metrics are established for internal usage, it’s then time to win over the external stakeholders.

Clear Communication with External Partners

Most companies have a major disconnect between the way they strive for long-run growth internally, and the manner in which they are held accountable by external stakeholders (who tend to obsess over short-term financial metrics).

A perfect example of this disconnect is the concept of “acquisition addiction”: Is a given company growing via healthy, sustained means where customers are staying and buying repeatedly, or is the company growing only through newly acquired customers, who then leave quickly? It’s obvious that a company should want to use the right internal metrics to diagnose such an issue and take action on it as quickly as possible. But shouldn’t external stakeholders want to do the same? They should be demanding to see such metrics in order to understand the sustainability of the company’s revenue stream instead of running the risk of being fooled by ineffective customer growth at all cost.

We believe that the metrics associated with customer centricity can create a natural alignment to get internal and external stakeholders to agree on metrics that are helpful for day-to-day operational purposes as well as the evaluation of a firm’s long-run health. That’s the beauty of focusing on a forward-looking metric like CLV—it is the right ingredient to achieve both goals. We’re already seeing a number of venture capital firms and even some private equity shops that use a CLV metric to help in their diligence process for prospective investments and also to compare the ongoing performance of their existing portfolio companies. This is a very promising sign and is the main focus of Peter’s new firm (Theta Equity Partners).

Of course, it is still very early days for external stakeholders to rely on customer metrics to do their jobs, but times are changing in this regard, and we believe that a day will come when external people and firms not only begin to deeply understand such metrics but also start to demand them.

In a similar way, Agile took decades to take root and gain widespread adoption. Even before the 2001 Agile Manifesto was published, there was a groundswell of activity in the software field that attempted to make existing practices less burdensome. For example, Scrum’s iterative process was launched in the 1990s and is now the gold standard for how to enact the points laid out in the manifesto.

“We believe that the metrics associated with customer centricity can create a natural alignment to get internal and external stakeholders to agree on metrics that are helpful for day-to-day operational purposes as well as the evaluation of a firm’s long-run health.”

Summary:

- You can leverage an iterative, best-practice framework to help you create a transformative plan for a customer-centric strategy. The Agile methodology is especially apt for this process.

- The Manifesto for Customer Centricity—inspired by the Manifesto for Agile Software Development—celebrates customer heterogeneity, cross-functional uses of CLV, metrics that reflect customer equity, and clear communication with external stakeholders.

- Drawing on Agile or another iterative, best-practice framework will help leaders regularly collect and analyze performance data during a customer-centric transformation, provide opportunities for consistent and transparent communication, and gain buy-in across the organization.