Breakthrough Technologies Don't Create Transformative Growth. Breakthrough Business Models Do.

July 11, 2018

"Adding digital capability to a product or to an entire business may improve it and make it more profitable, but technology alone is not enough to propel the kind of sustained growth that can transform your whole enterprise. The business model that goes with that technology is absolutely key to its success or failure. This was true when Amazon sold its first book online in 1995, when Netflix shipped its first DVD in 1998, and when Apple launched its revolutionary iPod in 2001. It was true in 2011, when Uber dispatched its first car, and it is even more true today. But it is still not widely understood."

Technology alone is not enough to propel the kind of sustained growth that can transform your whole enterprise.

Adding digital capability to a product or to an entire business may improve it and make it more profitable, but the business model that goes with that technology is absolutely key to its success or failure.

This was true when Amazon sold its first book online in 1995, when Netflix shipped its first DVD in 1998, and when Apple launched its revolutionary iPod in 2001. It was true in 2011, when Uber dispatched its first car, and it is even more true today.

But it is still not widely understood.

Technology is a Means to An End

Of course, a new technology can and often does enable business model innovation, but no matter how sophisticated and miraculous that technology might be, it is merely a means to an end, not an end in and of itself.

It wasn’t the iPod’s technology that upended the music market. Diamond Media and Best Data, among a number of other companies, had introduced their own snazzily-designed MP3 players to the market, long before Apple did. It was the business model that Apple wrapped around the iPod.

The iTunes Store was a unique service component that tightly locked hardware, software, and digital music into one user-friendly package. It couldn’t have existed without technology, but it is also evocative of King Gilette’s decision, all the way back in 1901, to give away razor handles (durables) for free, in order to lock customers into purchasing his consumable, high-margin safety blades. Apple reversed Gillette’s model, virtually giving away the blades— low-margin, consumable songs—to lock in the purchase of the handle, the iPod itself, whose high margins returned high profits. Amazon pulled off a similar trick when it brought its Kindle to market in 2007. Other companies, like Sony, had been selling digital readers with limited success for years, but Kindle owners enjoyed instant, one-click access to Amazon’s millions of titles.

Giving a refrigerator the capability to take an inventory of its contents, or a wristwatch the ability to monitor its wearer’s blood pressure doesn’t guarantee that consumers will line up to buy them, no matter how well they work. New technology can no more ensure success than stamping “new and improved” on the packaging of an outdated product can inoculate it against competition from cheaper, easier-to-use, or just plain better alternatives.

Customer Value Comes First

Netflix and Amazon were among the first retailers to open up their doors online, but their success flowed from the customer experience that they delivered. Getting DVDs from Netflix was less of a hassle than going to Blockbuster (never mind having to pay its late fees). Amazon was more likely to have the title you were looking for than your corner bookstore, and at a better price.

As sophisticated as Uber’s software may be, combining GPS tracking, billing, and logistical capabilities in one easy-to-use interface, in its essence the company is a glorified radio cab dispatcher. What propelled its rocket-like growth was the value and convenience it offered to its prospective passengers (and the opportunities for freelance employment it provided its drivers). Absent a compelling customer value proposition, a powerful profit formula, and a set of key processes and resources that deliver the right product or service to the right people in the right way, even the most astounding new technology can fail to gain traction in the marketplace. But with a fresh new business model, even a mature product can have a second life.

What is the takeaway? That disruptive technology startups needn’t have a monopoly on transformative innovation. Big, established corporations can conceive, implement, test, and roll out world-changing products and services just as well as or even better than high-tech startups do, if they would only muster up the will to venture into the uncharted white spaces where new opportunities lie.

Where is Your White Space?

The term white space has been used before in business parlance to mean uncharted territory or an underserved market. But I use it to refer to the range of potential activities not defined or addressed by the company’s current business model; that is, the opportunities that exist outside its core and beyond its adjacencies and that require a different business model to exploit. It’s an area where, relatively speaking, assumptions are high and knowledge is low— the opposite of conditions in the company’s core space.

Consider Lockheed Martin. The company excels in the relatively low-volume, high-margin world of multibillion-dollar fighter aircraft, missiles, and space satellites. It’s mostly served one primary customer—the U.S. government—and its core is built on delivering complex solutions in a highly structured way.

Seeking new growth markets, the company has invested over $100 million to build a heliumfilled “hybrid airship” unlike anything ever before built. The airship can take off and land in small, unimproved spaces and carry a very large payload.

To be successful. this foray into Lockheed’s white space requires a departure from its traditional assumptions about how to make money and from whom, using which resources. The company has created a new business model, targeting an entirely new customer—mining companies, freight companies, and others who need to transport huge payloads of cargo. Lockheed launched a new division, Hybrid Enterprises, with the new sales and distribution capabilities needed to sell the $40 million dollar airship.

The Four-Box Business Model Framework

A business model is a representation of how a company creates and delivers value for a customer while also capturing value for itself. This is fundamental, but many companies struggle to articulate their business models clearly, know their strengths and weaknesses, or understand when they need a new model to deliver on a new opportunity

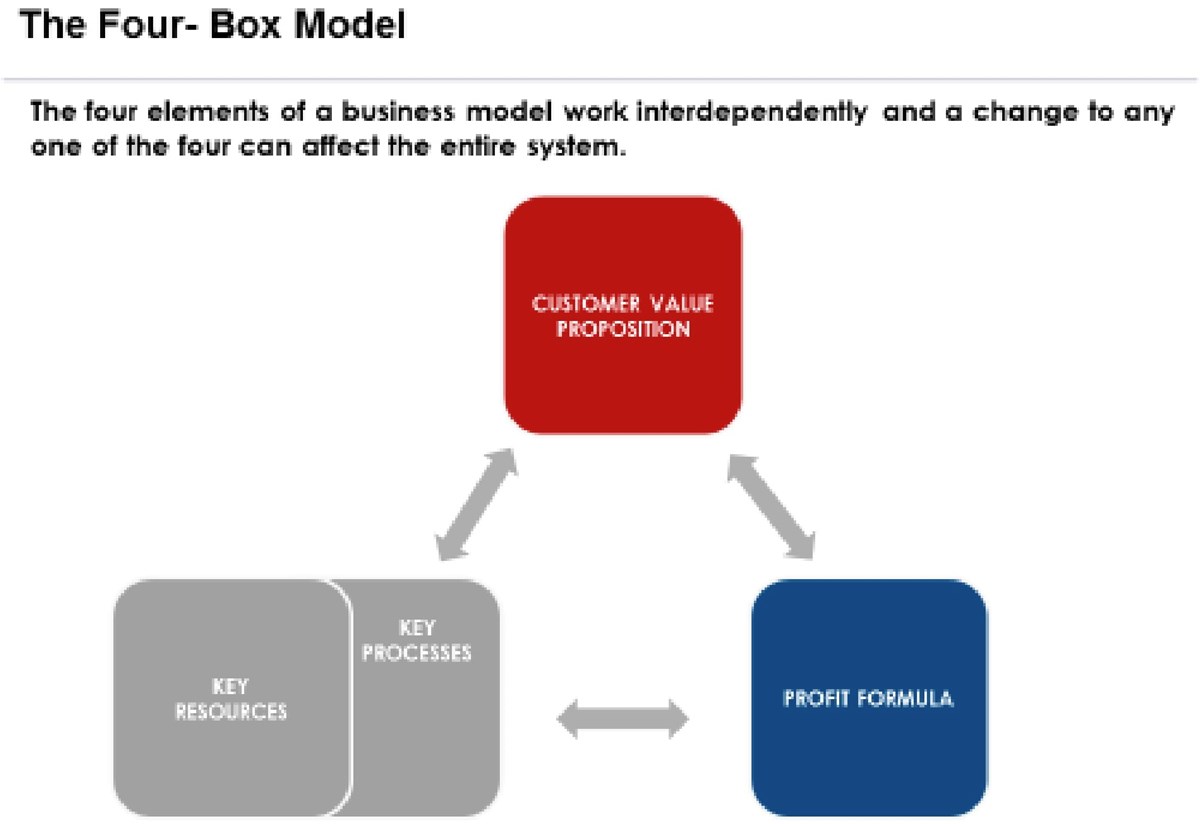

Part of the problem is the lack of a shared vocabulary. To render the most essential elements of value creation in clear language, I propose a four-box framework, which I believe provides the structure that is needed to surface and categorize all the issues that must be addressed before a company can confidently venture into the low-knowledge, high-assumption environment of its white spaces.

Every thriving enterprise is propelled by a strong customer value proposition (CVP)—a product, service, or combination thereof that helps customers more effectively, conveniently, or affordably do a job they’ve been trying to do. Back when Whole Foods was still a local chain of health food stores, it realized that upscale foodies and people who care about the environment would be as willing to pay a premium for organic produce and sustainably-produced meats and fish as its current customer base. So it reached out from its crunchy-granola core to a new customer with a new job-to-be-done:

“Give me full and pleasurable access to a variety of foods and products that meet my high standards for quality and honor my interests in health, organics, and protecting the environment.”

The profit formula defines how the company will capture value for itself and its shareholders. It does this by distilling an often-complex set of financial calculations into the four variables most critical to profit generation: a revenue model, cost structure, target unit margin, and resource velocity. Amazon was able to charge as low prices as it did in the beginning, despite its low volume, because its customers paid for their purchases with credit cards, putting money into its hands immediately. This gave it a float that allowed it to hold customer’s money in its hands for an average of 41 days before it had to pay its suppliers.

Finally, key resources and key processes are the means by which the company delivers the value to the customer and to itself. These critical assets, skills, activities, routines, and ways of working are what enable the enterprise to fulfill the CVP and profit formula in a repeatable, scalable fashion.

The power of this deceptively simple framework lies in the complex interdependencies of its parts. Successful businesses devise a relatively stable system in which these elements interact in consistent and complementary ways. A change to any one of the four affects all the others and the system as a whole. Incongruities or conflicts between elements, even seemingly inconsequential ones, can bring about its downfall.

The Existing Rules, Norms, and Metrics Can Kill a New Business Model

The business rules, behavior norms, and success metrics that help to make an existing business model successful can be poison to new business models. They act as invisible guardians of the current model and can undermine nascent efforts in a myriad of ways:

- Limiting how far a project team will venture from traditional offerings, precluding new approaches to what can be sold (such as moving from a product to a service) or how an offering can be sold (such as moving from physical stores to the internet).

- Creating an organizational urge to “cram” new opportunities into the existing business model.

- Prematurely pressing for growth at the pace and on the scale of the traditional core.

- Maintaining a rigid adherence to the current profit formula—for example, expected margins of the core enterprise can lead executives to reject out of hand the possibility of reinventing a business model with different margins.

But leaders can learn to recognize and overcome the influence of existing core business models in the pursuit of their corporation’s white spaces. Some ways they can do this:

- Create a strategy development process that is unfettered from the assumptions that drive its core.

- Establish dedicated teams to create new models and then protect and nurture them. Such teams should not be large, but they do have to be focused mainly on the new.

- Empower these teams to create new rules and metrics, especially financial metrics.

To Be Built to Last, a Business Must Be Built to Transform

No company, no matter how successful, can escape the need to change. Shorter business life cycles require a new sort of management discipline that is capable of leading organizations through a continual process of transformation and renewal. To be built to last, every business must be built to transform.

Once the archetypically brash startup, now one of the biggest and most formidable companies in the world, Amazon has become the paradigm of a serial business model innovator, from e-books to Cloud services; from original TV entertainment and robotics to fulfillment and logistics, and from grocery stores (virtual and, with its recent purchase of Whole Foods, bricks-and-mortar) to health care.

“If you want to continuously revitalize the service that you offer to your customers,” its founder and CEO Jeff Bezos notes, “You cannot stop at what you are good at. You’d have to keep asking what your customers need and want, and then, no matter how hard it is, you’d better get good at those things.”

To understand the structure of a business model well enough to build them repeatedly, business leaders must learn to think like architects and engineers, beginning with blueprints, building prototypes, and then developing working structures that can deliver on new areas of opportunity.

Business model innovation thrives in cultures of inquiry, environments in which new ideas are met with interest and encouragement. “Controlling innovation is an oxymoron,” says Netflix CEO Reed Hastings. “You inspire innovation. You support innovation. Unlike the quality process, where the goal is to reduce variability, innovations require you to look for ways to increase variability. And business model innovation is scary because it is the toughest to take on.”

It doesn’t have to be. The four-box structure helps make business model innovation into a core management discipline—a relatively predictable and repeatable process that can be learned and mastered. Risky, yes—but a far cry from a leap into the unknown. To meet the growth gaps, market shifts, uncontrollable social forces, and technological disruptions that the future is sure to bring, every business leader must learn to seize the white space through business model innovation.